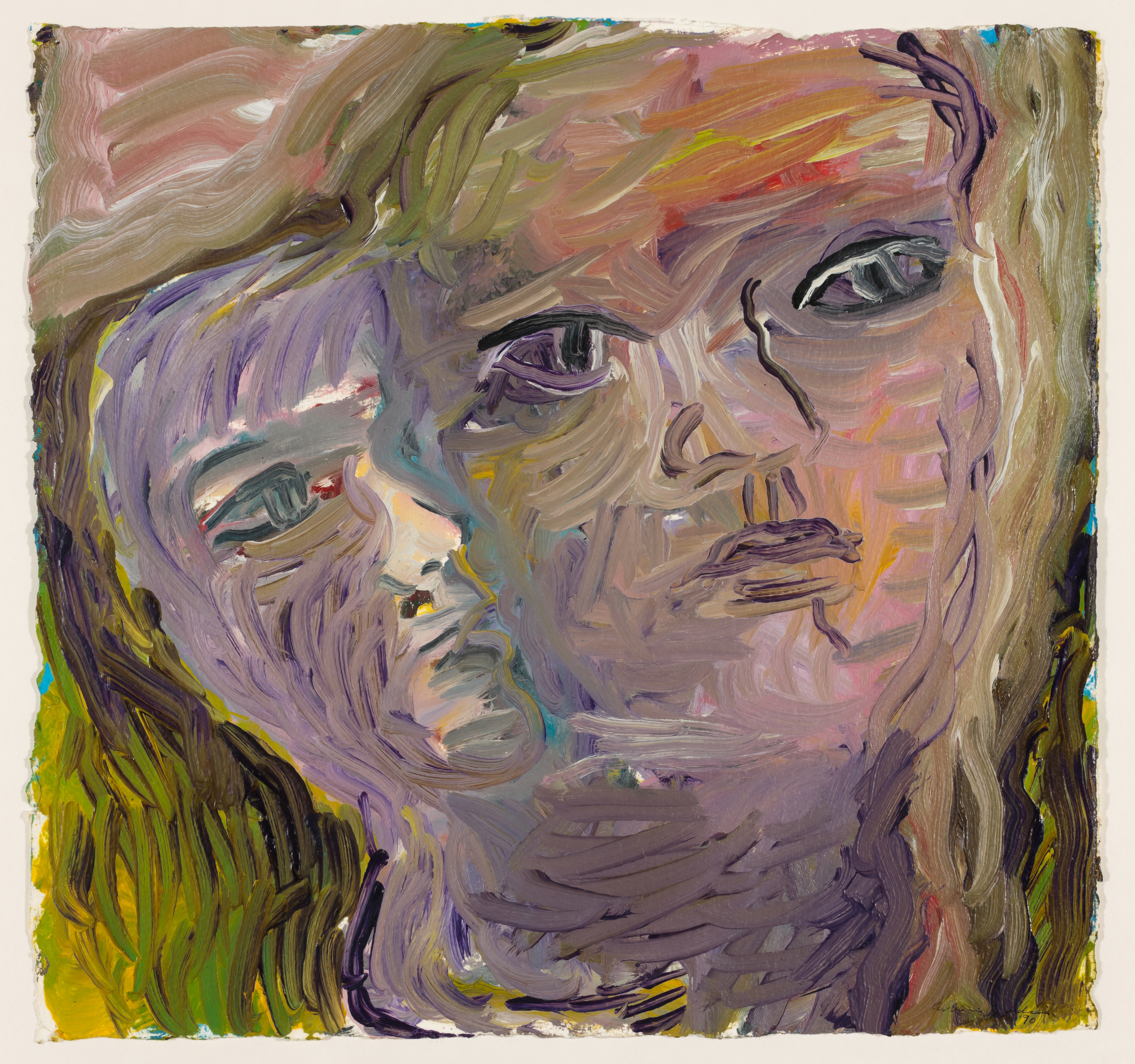

Eithne

Jordan Shelter 1V, 1990. Oil on paper,55 x 58 cm. Collection of the Arts

Council/An Chomhairle Ealaíon

Eithne

Jordan Shelter 1V, 1990. Oil on paper,55 x 58 cm. Collection of the Arts

Council/An Chomhairle Ealaíon

What we

see in Colm Bairéad’s film ‘An Cailín Ciúin’, based on Claire Keegan’s story

‘Foster’, is not only how quiet and self-contained the young girl is – she is

played by Catherine Clinch - but how much she notices and takes in. She is a

watcher and, in the story, as in the performance, we get a sense of how much

work it takes for her to disguise her sharp intelligence, to pretend that what

is happening is nothing much.

At the

heart of the drama is a sense of displacement. The young girl has to navigate a

new world filled with secrets and suppressions, in which every single thing,

down to the smallest gesture, is fully defamiliarized, and has to be noticed as

though for the first time, as if everything depended on it.

The young

girl must read the world as strange text. She displays her puzzlement, her

knowledge, her understanding, by remaining still, by saying nothing, by the

evenness of her gaze. She gives nothing away. It is part of the genius of the

film, and indeed the story, that this idea is trusted and made powerful.

The drama

depends on the quality of the girl’s solitude. It is essential that she is away

from friends and siblings, under the control of adults who are new to her.

It is

interesting that there are a number of other stories that have some of the same

qualities as ‘Foster’ and also deal with the tense inner life of a young girl

or a young woman.

Maria

Barbal’s ‘Stone in a Landslide’, for example, written in Catalan, published in

1985 and translated into English in 2010, tells the story of Conxa who, at

thirteen, is taken from the house of her family to the house of her childless

aunt and uncle. Although she marries, and has children, and suffers loss in

wartime – the novel is set in the foothills of the Catalan Pyrenees in the

period around the Spanish Civil War – her consciousness remains tender, raw.

The

language in which Conxa thinks and notices is remarkably simple and unadorned,

which, oddly enough, allows the reader to see her as a figure capable of deep

and complex emotion. The years, as she describes them, seem like time in a

folk-tale as much as time lived in history. What happens is rendered as though

much of it were inevitable, like something preordained. But this is merely a

way of keeping the real pain of other, unexpected, things at bay.

At the

beginning, in her new life, Conxa notices the smallest object or aspect of

nature or of people’s moods. No emotion is ever heightened or given more colour

that it should have. This means that certain moments in the book, because of

the calm precision of the writing, and the sense of resignation with which they

are described, have a sort of piercing truth.

‘The

Swan’ by the Icelandic novelist Gudbergur Bergsson was first published in 1991

and translated into English in 1998.

At the

beginning of the novel, a nine-year-old girl, like the girls in ‘Foster’ and

‘Stones in a Landslide’, is taken from her home. The girl’s life is in

suspension. The act of making sense of things gives her a special energy. If

she went home, she would have to confront what was once familiar. By staying

away, she inhabits strangeness, and her own solitary spirit becomes the richer

for that.

In ‘The

Swan’, the fragile growing consciousness of the young girl has a sense of

hard-won truth. Each moment of noticing has to be done with care; the gaze is

wary rather than direct or fearless. Silence has more power than speech. The

half-understood has more texture than the fully explained. The very fragility

of the narrative, the fact that nothing can be taken for granted, offers the

work a nervous and shimmering force.

It

matters, I think, that all three writers – Keegan, Barbal and Bergsson – are

writing about northern light, northern weather. Ireland, the Catalan Pyrenees

and Iceland have their unhospitable seasons; they are places where the light is

scarce and the spirit is wary and the past comes haunting and much is

unresolved.

The

presence of weather is important in these books. But more than anything these

narratives from rural Ireland, rural Catalonia, rural Iceland can manage

sorrow, can deal with loss and absence and loneliness as it is experienced by

one solitary consciousness, as though there was something in both the culture

and the natural world which allowed for this and made space for it.

In all

three short novels, there is a sense that we are in a world that has been

untouched by the twentieth century in some of its more obvious manifestations,

one of which is irony or distancing effects. This is a world that is not adrift

with images of itself, which has not been filmed or much photographed. It is a

place where silence cannot merely still be heard but can hold sway over much

that happens. It is a place where people still watch from windows, where

community is both intact and fractured, where the young girl, the one who has

been displaced or abandoned, is never sure whom she can trust and thus has to

learn to question even her own perceptions.

What

connects ‘Foster’ with ‘Stones in a Landslide’ and ‘The Swan’ is also the sense

of narrative as a slow-moving camera or a set of scenes captured by a painter

of still lives in a northern landscape whose palette is filled with muted

colours.

The world

is being held in images that are not fleeting, or part of a continuum, but

caught only once before they are replaced. Because of the simplicity with which

time is handled in these books, with scarce recourse, for example, to the

pluperfect, the present scene has to imply a great deal. The present moment is

watched with nervousness and unease.

The

presiding consciousness seldom weighs up consequences, or thinks of complex

strategies or works out in any details how her desires might be fullfilled, or

her fears kept at bay. There is a single pleading note at the heart of the

young girl’s perception. A stillness. She takes an extraordinary and unusually

intense interest in the scene in front of her and the sounds she hears. It is

as though her eye is all camera, there to record and frame the scene so that it

can be studied later, or as though she is a painter finding accurate colours in

which to hold and contain experience so that it can do no further damage to

her.

All three

short novels, while insisting on particularity, manage to have a force that is

suggestive, almost symbolic, as if the minutely-observed, closely-held universe

represented something beyond itself, waiting to find an image which would free

it and offer it some resolution, however fleeting and isolated and strange.

Colm Tóibín (October 2022)