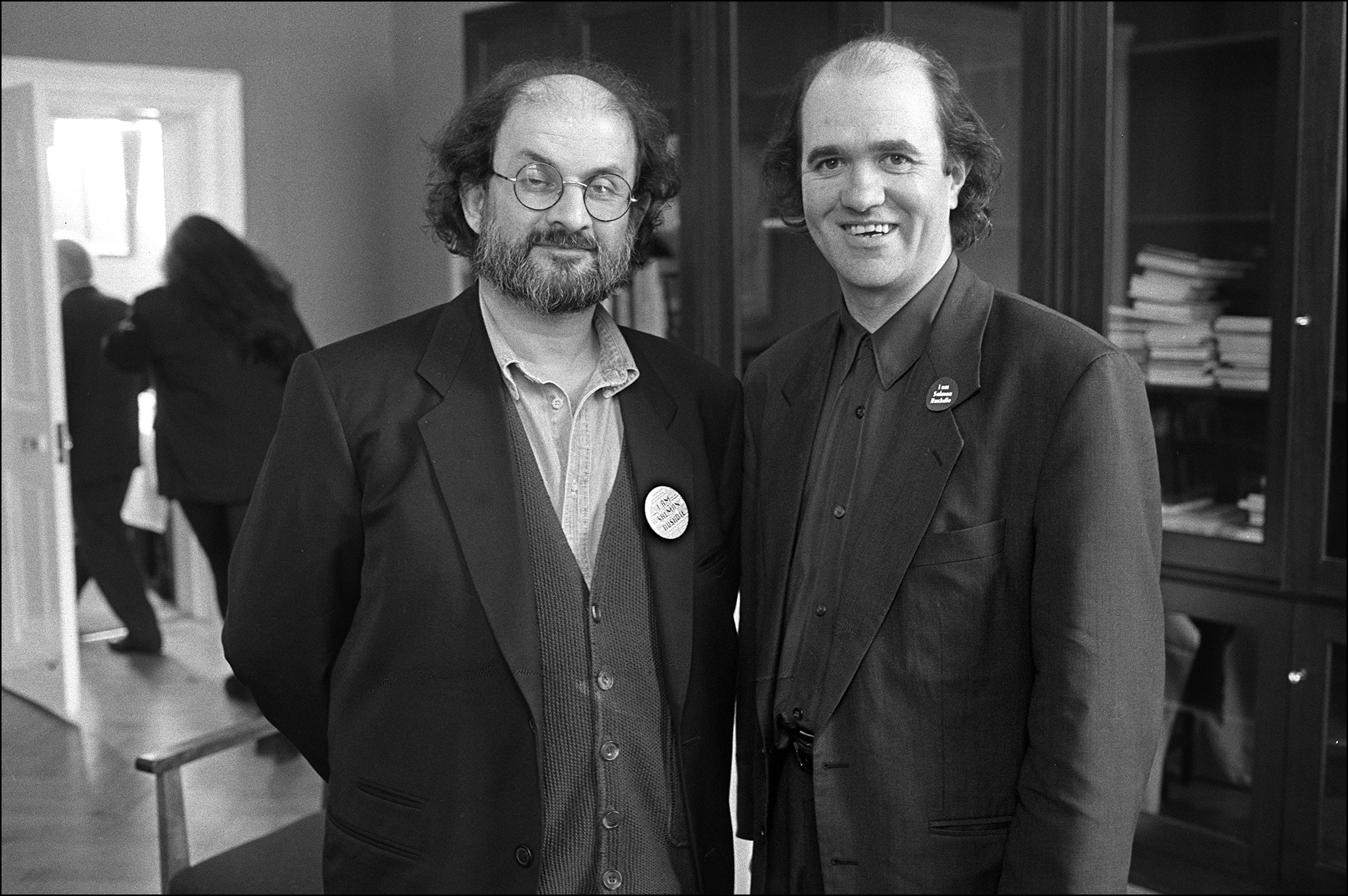

Salman Rushdie with Colm Tóibín at the Arts Council offices, January 1993. Photo: Derek Speirs

Salman Rushdie with Colm Tóibín at the Arts Council offices, January 1993. Photo: Derek Speirs

On November 8 2016 I bumped into Salman Rushdie at a party in New York. He was wearing a broad smile. He had, that day, voted in America for the first time. That night, it was still presumed that Hillary Clinton would win the election.

Salman Rushdie felt good about becoming an American citizen. New York seemed to suit him. I was amazed the first time I had dinner with him in the city that he seemed to arrive with no obvious security and he appeared to be able to leave without having to notify minders. I wondered if he had worked out a way of keeping safe but making no fuss about it. I didn’t ask. He was not interested in talking about his own safety or the risks he took.

In America he had become, among other things, an activist. As President of PEN America when the attacks on 9/11 happened, he realized that America was likely to become more insular, more paranoid about the outside world. Even New York could become more fearful. It was for that reason that he founded the PEN World Voices Festival in New York with the aim of inviting as many writers as possible from all over the world to America, to make sure that the xenophobic agenda being pursued by the Bush administration did not prevail in New York.

In 2004, Rushdie organized a reading in New York with the title ‘State of Emergency’, with writers who opposed the more vehement forms of censorship emerging in the US. ‘People come to the United States because they admire freedom of expression. It’s what attracted me here. It’s a tragedy to think that that has been threatened,’ Rushdie told the French newspaper Liberatión, who reported: ‘Before arriving on stage, Salman Rushdie denounced the Bush administration’s increased control over the media.’ Rushdie said: ‘For 82 years, PEN has fought for this freedom in other countries. It is important not to ignore the problem when it arrives at our doorstep.’ In 2010, Rushdie described America’s discourse with the rest of the world as ‘a dialogue of the deaf.’

When I saw him in those years Rushdie was cheerful and relaxed. Since everyone noticed him coming into a room, he had a way of remaining reserved, almost distant. He was, as the years went on, a public figure in New York, someone concerned more with freedom of expression than he was with his own plight. This made

it easy to feel that the danger he had been in was now less pressing.

In the time when he was still living under vigilant protection in the UK, I had two interesting encounters with him. In January 1993, four years after the fatwa, Rushdie came to Ireland. Some time before that, when I met him in London, he told me that he had been in touch with Dick Spring, then Minister for Foreign Affairs, about the possibility of travelling to America using Aer Lingus, since most of the British carriers were refusing to take him across the Atlantic.

In Dublin, it was clear, he wanted to see as many people and places as he could. He was received by Mary Robinson. He gave a speech in Trinity at a conference on press freedom called ‘Let In The Light’. He went to Joyce’s Tower. And, at the invitation of Dermot Bolger, then a member of the Arts Council, he came for lunch to meet Irish writers in the Arts Council building in Merrion Square. I remember Michael Hartnett there, and Anthony Cronin, and I sat between John Banville and Hugo Hamilton.

At some stage before the visit, someone asked me if I could think of something that Salman would like to do on a Saturday afternoon in Dublin in January. I can’t think what came over me but I suggested that since he had been cooped up for so long that he might enjoy a walk on Howth Head. There was much consultation with the Gardaí and the Special Branch who agreed that they could provide ample security for this walk.

Salman by this time had become used to being driven places. Even as we made our way out by the North Strand, he didn’t enquire where he was going or why. The sky was blue and it wasn’t too cold. He was placid and interested in everything. He asked me if John Banville came from an aristocratic family.

Once on the Head of Howth, I realized that he believed he was going somewhere, that there was an actual destination.

‘Is it always as windy as this?’ he asked as the sweep of Dublin Bay appeared before us. The view really was magnificent. The only problem is that Salman Rushdie was not, is not, and never has been, interested in scenery. It is not his thing. He loves culture and complexity, he is a chronicler of teeming cities and happiest in the great ones – London, Bombay, New York. His abiding interest is what happens, in our time, to cultures under pressure.

There was no culture on Howth Head and the only pressure was to get our guest back to the city as soon as possible. He did become animated when he was told about Leopold Bloom and Molly courting in this very place, and he became even more engaged when I showed him Conor Cruise O’Brien’s house on the Summit. He wanted to know how much time the Cruiser, as he was called, spent there. I think he thought that it was strange for someone to choose to live in such a windswept place. But he was unfailingly polite, so I never did find out what he thought.

I just guessed. And I guessed he was relieved driving back through busy city streets.

When his next novel ‘The Moor’s Last Sigh’ came out, as I travelled with him on part of his book tour to write a profile for Esquire, I didn’t ask him what was the worst aspect of the fatwa. I was worried that he would say that it was that terrible walk on the Hill of Howth.

In January, for God’s sake!

On that book tour we were accompanied most closely by two of Rushdie’s security team. One was doing, as a hobby almost, a PhD in English. The other had just won a whole wardrobe of clothes in an Esquire competition.

Sheepishly, I didn’t deny that I had something to do with Esquire competitions, and this won me great favour in the car as we travelled to a literary festival with our star author.

Salman Rushdie has one great flaw. He had never finished George Eliot’s ‘Middlemarch.’ And he doesn’t seem to feel guilty about this. In the car, myself and the cop who was also doing a PhD discussed the sheer sweeping greatness of the book.

All this meant that on the journey from London to Cheltenham, Salman Rushdie didn’t have to answer any questions about the fatwa. As the two cops and myself grew more fired up on the subject of Esquire competitions and the marriage of Dorothea to Casaubon, Rushdie sat there quietly.

He seemed content to be let alone.

Colm Tóibín (September 2022)