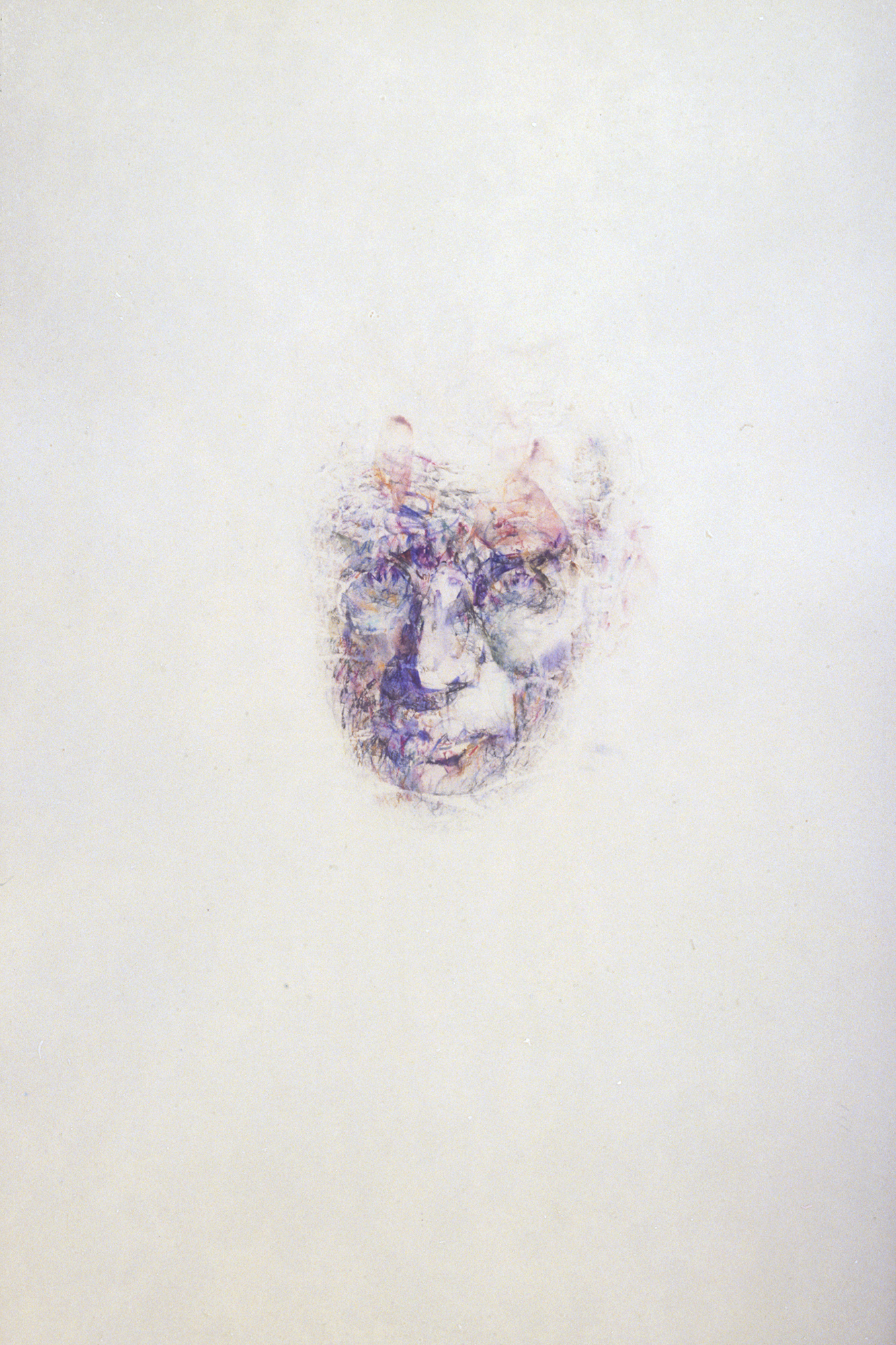

Louis Le Brocquy Image of Samuel Beckett,

1987. Watercolour on paper. 71 x 51 cm. Collection of the Arts Council/An

Chomhairle Ealaíon

It is 1962 and my father is doing what I am doing now – he is at

a table, writing; his head is down in concentration, his right hand is moving

slowly across the page. There is chaos all around him, books piled on the floor

and on the table, and notebooks open, as there is untidiness here as I write

this. Sometimes when my father reads over something and doesn’t like it he

crumples up the whole page and throws it towards the fireplace, often missing.

I try not to do that, but I often find that my effort to be more tidy has

failed. I also write in longhand. My handwriting is clearer than his was. Or

else: his handwriting might have looked clear to an adult, but not to a child.

I wonder if I watched him writing and thought that I could do

that too. But we all have our own reasons for writing. Some days a phrase

comes, or a sentence, or even an image. Or a problem in the construction of a

novel arises, worries me, and I set about resolving it, at least for the moment,

as though it were a problem in mathematics or structural engineering. This is

not something I inherited or took from another person, even a parent. It comes

from something more hidden, deeper, more personal and essential.

But that image of my father is powerful, haunting. I must have

learned something from it, soaked in some of its energy.

In 1967 the American novelist James Baldwin wrote: ‘The

father-son relationship is one of the most crucial and dangerous on earth, and

to pretend that it can be otherwise really amounts to an exceedingly dangerous

heresy.’

It seemed important, however, for both James

Baldwin himself and Barack Obama too,

as they

both wrote their autobiographies,

to establish before anything else that their story began when their father died,

to emphasise that they set out alone without a father’s shadow or a father’s

permission. Baldwin’s ‘Notes of a Native Son’ begins with his father’s

death when he was almost nineteen.

Barack Obama’s ‘Dreams from my Father’ begins also with the death of his

father: ‘A few months after my twenty-first birthday, a stranger called to give

me the news.’

Both men quickly then

established their own actual distance from their father, which made their grief

sharper and more lonely, but also made clear to the reader that they had a

right to speak with authority, to offer this version of themselves partly

because they themselves, through force of will and a steely sense of character,

had invented the voice they were now using, had not been trained to be the

figure they had become by any other man.

‘I had not known my father very well,’ Baldwin wrote. Barack Obama

wrote: ‘At the time of his death, my father remained a myth to me, both more

and less than a man...as a child I knew him only through the stories that my

mother and grandparents told.’

For other sons, the father was

fully present and became an important and an abiding inspiration. Sometimes,

nonetheless, the son learned to fulfil the father’s dreams without following

his example. Both Henry James and his brother William, for example, finished

everything they began. This was in sharp contrast to their father who was a

great talker, but did not complete much. So, too, the father of the poet W.B.

Yeats and his brother the painter Jack B. Yeats, who were also great workers,

was good at making plans, but bad at carrying them out. It was as though the

sons took what they needed from their father, his talent, and then set about

offering it a completion. Their work, in all its steadfast relationship to

reality, was a sort of homage to their father, but also came as a dispute with

him and his indolence.

Images in literature about what

the loss of a father means to a son make clear how close the bind is, or how

much the father represents an anchor for a son, someone who holds the world in

place. It is easy to see Hamlet as the play begins, for example, as a son made

wayward by his father’s death. He can be in love, and the next minute

out of love, and then angry and ready for revenge and then ready to

procrastinate, the next minute melancholy and the next putting an antic

disposition on. Hamlet’s tone can be wise and then bitter and sharply sarcastic

and rude. How can he be so many things? Because his father has died not long

before. That is all. He has been unmoored.

Are there any examples, on the other hand, in literature or in

the lives of writers, where the relationship between father and son is simple

and filled with love and ease, where one generation hands on to the next with

no tension, just loyalty, where memories and the experiences that gave rise to

them are sweet and easy? Yes, indeed, there are such examples, and in the most

unexpected places. Samuel Beckett, to take one, and his father felt mutual

affection and ease and love. In Beckett’s letters, and even in his late work

‘Company’, he lets us know how much he admired his father who was a

quiet-living, non-literary, quantity surveyor in Dublin. Beckett relished the

long walks they took together in the mountains south of Dublin. In April 1933, for example, he wrote to a friend: ‘Lovely walk this

morning with Father, who grows old with a very graceful philosophy. Comparing

bees and butterflies to elephants & parrots & speaking of indentures

with the leveller. Barging through hedges and over the walls with the help of

my shoulder, blaspheming and stopping to rest under colour of admiring the

view. I’ll never have anyone like him.’ Four months later when his father died,

he wrote again: ‘He was in his sixty-first year, but how much younger he seemed

and was. Joking and swearing at the doctors as long as he had breath. He lay in

bed...making great oaths that when he got better he would never do a stroke of

work. He would drive to the top of Howth and lie in the bracken and fart…I

can’t write about him. I can only walk the fields and climb the ditches after

him.’

On New Year’s Day 1935, in

another letter, Beckett remembered a Christmas morning ‘not long ago standing

at the back of the Scalp with Father, hearing singing coming from Glencullen

Chapel. Then the white air you can see so far through, giving the outlines

without the stippling. Then the pink & green sunset that I never find

anywhere else and when it was quite dark a little pub to rest & drink gin

in.’

These are the memories that sustained Beckett, the sort of

memories that belong to us all, or those of us who have been lucky enough to

have known and loved a father. They belong to me too as I put down my pen now

and turn and look and see my father, oblivious to everything, having filled a

new page with words, and then stopping to check over what he has written, and

putting the pen towards his lips as he reads his own words, making a change

here and there, the floor around the fireplace dotted with the pages he has

abandoned. We turn towards each other. There is so much to say.

Colm Tóibín (April 2022)